rewritten by Cheryl Petterson

originally published as "Incident"

Return to Valjiir Stories

Return to Valjiir Continum

She had asked for leave on religious grounds, a thing that could not be denied by Starfleet except for an act of war or intragalactic emergency. The Captain hadn’t even asked for an explanation, though it was his right as her commanding officer to do so. Sulu had, of course, but she could not bring herself to tell him. They’d argued about it until she had at last begged him to simply trust her. I will be gone no more than a week, she had promised him. And he had sighed unhappily, but let the matter drop.

Jilla Majiir piloted the Chutzpah on sheer instinct, the course locked into the navigational system. She had spent the three days to Indi curled inside the deepest Vulcan trance that still left her functional, and only took the controls fully when she reached atmospheric insertion. The craft settled beautifully onto the port-dock at Rilemi, and she gathered all her strength before forcing Vulcan control away. She could not allow herself the shield, to do so would be blasphemous. It would mock what she had come to do. The irony of that thought was not lost on her, and she was shaking as she stepped to the shuttle’s hatch. She closed her eyes as it opened. She had received special clearance from the port authorities, and so knew there would be a crowd to receive her, Indi’s honored daughter. Bowing her head, she unclenched her left hand, bringing it palm forward against her right shoulder, the proper acknowledgement of her sin. She walked onto the soil of Indi for the first time in seven years, knowing it would be the last.

The gasps were automatic, and Jilla fought to receive the rush of anguish with no barrier. A hundred souls screamed in immortal terror, the left hands of those mnorindar were pressed hurriedly to crying hearts. Her shame echoed and reverberated between them and her, multiplying with horrified agony. Spreading, it called every Indiian to bear witness to the damnation of telmnori.

Jilla did not speak, could not, as the cold slowly replaced her ever-present pain, a torment she knew she would bear for the rest of eternity; non-being, non-existence, non-acknowledgement. She descended into an icy prison which would forever separate her from worth, from family, from peace, from Aema’s care. She moved steadily forward, her steps measured torture. One was required to walk in the ceremony of telin-arin, to feel fully the weight of one’s sacrilege. She focused her mind on the ritual, letting the agony tear at her as was proper, the emptiness mending the pieces into a barren place of sunless isolation.

It was perhaps a mile to her parents’ home, a mile that took the eternity she had desecrated to cross. Her palm was burning, the torment of each pair of eyes searing the ice of Beggar’s Court deeper along the dark scar. Her eyes had long since ceased seeing, her ears no longer heard the pleas to Aema that wailed at her approach. Yet still the pain and despair cut into her, cold, hard rejection, terrible, numbing nothingness.

She waited when she reached her family’s door, steeling herself for the second part of the ritual. There was no need to knock. Her infidelity called to her mother as it had to every other Indiian, especially so as Karina was, for the Costain household, Aema’s representative. The door opened, Karina’s cheeks tear-stained, Kera, who was but twelve crying behind her. Weep for my pain, my sister, Jilla thought with misery, for soon you cannot, will not. She swallowed, then looked up, meeting Aema’s judgment in the eyes of her mother.

The glacial fury welled in Karina’s eyes, making them cold steel. Aema’s voice spat, “Telmnor!!” It carved damnation into Jilla’s soul, as it was meant to. Jilla lowered her head, acknowledging, accepting, then turned in silent, solitary suffering, heading for the next step in the ceremony. She was Duné, of the Imperial line, and so must present her shame to First Emperor Thaeré and the Council.

Again she walked, slowly, stately, but with no pride or peace. The flame in her palm was stronger, growing with each moment, sending pain shooting up her arm and into her soul. The void around her grew colder, more enveloping.

No courtier barred her way, no guard dared to announce her. She stepped into the throne-room, kneeling as was proper for a woman, careful not to block her palm from their view. She saluted Emperor and Council, who stared, horrified at her. Renewed waves of torment poured into her, more ice, more crushing nullity. Bolt after bolt of freezing fire seared into her hand, and she began to tremble. She was near the end, but she knew too well she would endure the guilt and emptiness of her shame always, even in Sulu’s arms. The thought of him intensified the emotions that beat at her, and she nearly broke as she slowly stood, turning from the Council as they turned from her.

One last agony, one last piece of ritual. She returned to her parent’s home, dreading this most of all. She did not enter, but made her way around the house to the garden, to the place where she had danced for the joy of belonging to Selar. As she stepped along the hard earthen path, the eyes and ice of nearly as many people as had been at her wedding ravaged through her being. Behind the altar at whose light she had vowed stood Karina, terrible, proud, Aema in all Her awful glory. Jilla approached, unable now to control her shaking, or the lost, anguished tears that stayed, crystal emptiness, in her eyes. The hollow in the stone still held the oil that had spilled from cups in Selar’s hand and hers, the oil that had flowed together with their blood and their lives. When Kera married, another hollow would be carved. But now, Jilla lifted her left hand over the oil, and with a cry that rent the heavens with purest horror, brought the burning flesh to that oil, scattering it in drops as severed as her faithfulness. The pain only raged stronger, and she fell to her knees, her arms extending upward in supplication and entreaty, a Beggar before her Goddess.

Karina turned her back, the final denial, and Jilla rose, the ceremony ended, and fled back to the shuttle port. She shouldered through the crowds of non-existence and had almost reached the relative safety of the Chutzpah, her mind ablaze with pictures of her mother’s next action: to retrieve her marriage parchment, tear it in half, and burn in what oil remained the portion that contained moon-symbols – and Indiian blood.

Then a voice called her name, deep, male and joyful, and she collapsed as her father raced to her from his diplomatic shuttle. She had timed the telin-arin to coincide with one of his diplomatic missions, not wanting to face him, and her thoughts screamed with fresh agony.

“Child you did not tell me…” he began, then stopped abruptly, gasping. The tears in Jilla’s eyes fell, released in glacial, barren shame.

“Telmnor, rosh,” she sobbed, and turned, trying to crawl from him. But his hand came to her shoulder, stopping her as he dropped to his knees beside her. He spoke in quick, anguished words, disbelieving, unaccepting.

“I knew your marriage was wrong,” he whispered, “I knew in my heart it would come to this. But you were a woman, how could I stop you? The fault was mine, child, I should have found a way!” There were tears in his grey eyes. “I know it cannot be,” he went on, his voice a rasp of grief, “but you are my child, my daughter, Jilla, and I love you still!”

She wept, shaking in his embrace, and he pulled away. His gaze searched hers, pained, aching. “Write, at Babel,” he murmured hoarsely, then rose and walked rapidly away from her.

She climbed back into the Chutzpah, her grief multiplied by his incomprehensible reaction. Yet she was grateful, almost deliriously so, for the touch of being he had given her, though she knew she did not deserve such a kindness. Her palm burned, the ache numbing her mind to all else. She quickly brought the shuttle up to power, lifting off, working feverishly to stay the empty cold. As the craft pulled away from her former homeworld, she did not presume to look back. On Indi, she had ceased to exist.

Spock sat in the con near the end of second watch, and for the first time that he could recall, wished for a duty period to end. He acknowledged that it was an illogical feeling – but there it was; almost physical, a heaviness, a feeling of being smothered in a coldness that crept up from his soul. Almost physical – yet he knew it was not. In a Human, he would have called it depression, but it wasn’t that, either.

With a mental shudder he forced himself from useless introspection and poised his finger over the log button, ready to make the watch entry. He asked for status reports from each station, in an orderly, clockwise fashion beginning with Communications, leaving Sciences for last. When over five minutes passed after the report from Life Support and Sciences did not respond, he turned his head to look at the young woman manning the station.

Ruth Valley sat limply, mouth slack, her right hand clutching fiercely at her left wrist. Her huge eyes were staring, full of anguished non-existence, a deadly pallor growing from pale tan to sick grey as he watched. How long has she been in such a state? was his first thought. His second was to wonder how he had gotten to her side without realizing he had moved from the con.

Concern stabbed through any occupation with decorum as he reached for her. Ruth? His fingers touched her balled left hand and she collapsed against him with a low moan, curling protectively around her fist.

He caught her and lifted her into his arms. She seemed almost weightless, and he had the startling impression that she was fading. He nearly ran to the turbolift to take her to Sickbay.

McCoy had been planning on saying something caustic to Spock about the inconsiderateness of pulling a man away from a card game he was winning. But as he entered Sickbay, he heard M’Benga telling the First Officer, “I’m sorry, Mr. Spock, but I can’t find anything physically wrong with her.” He saw the inert figure curled on the diagnostic bed. Biting back the foreboding that radiated from his gut, he shouldered past the two men.

“The answer has to be telepathic,” he heard himself saying. Gently, he turned Ruth to face him. Looking into her eerily open eyes was like falling into a pit of barrenness that was yet oppressively alive. He turned away, frightened and not knowing why. “Spock?” he croaked.

“It happened on the Bridge,” Spock answered. “It has been seven point three minutes since I noticed her condition. She is in pain,” he added, his tone admonishing the doctor to do something.

“What do you expect me to do, Spock,” McCoy snapped. “I can’t get into her head!”

“But you can, Commander,” M’Benga quietly reminded the Vulcan.

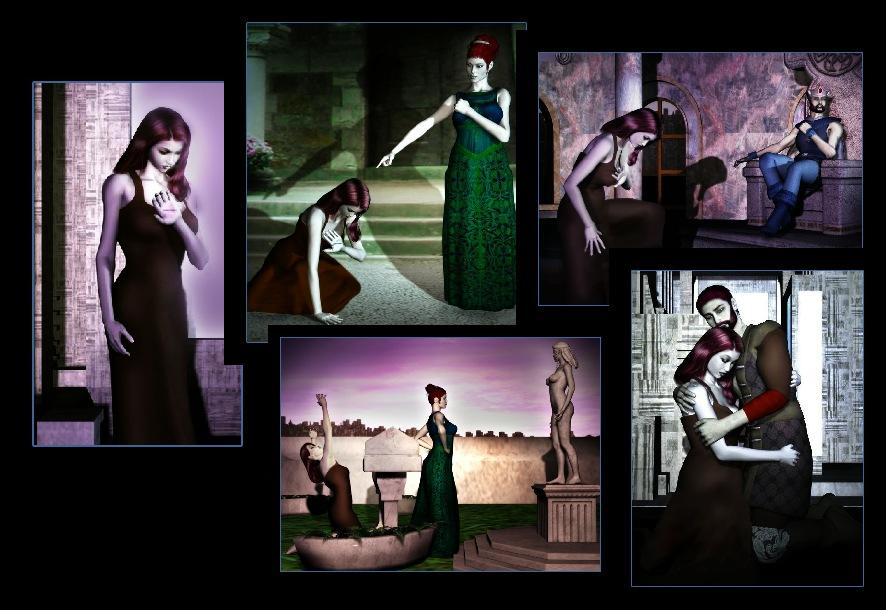

McCoy watched as Spock swallowed and nodded. He knew that such melds were profoundly disturbing for the Vulcan soul, but he also knew Spock could not easily let another suffer. After a moment’s grounding, Spock took a step forward, rubbing his hands together in preparation. As his fingers reached toward Ruth’s temple, his body stiffened with sudden rigor, a cry of pure, animal loss keening from his throat. His hand turned, palm upward, and he stared at it, as if there should be some horrible wound.

Spock moved with the same incomprehensible speed he had on the Bridge. One instant McCoy was shouting something, M’Benga pulling on his arm – the next he was clawing his way into Ruth’s mind without any memory of actually touching her. A hand slashed across his face and he reached up and, he didn’t realize until much later, nonchalantly snapped M’Benga’s wrist.

His fingers returned to Ruth’s temples of their own volition, and they were both encased in ice. Sentience at absolute zero, condemnation from countless separate beings. A billion grey eyes saw through them, each pair echoing shame, guilt, horror, using it as a blade to tear their souls open. Yet it was their anguish that wounded those billions of beings, their blasphemy that created the agony in their scarred palm. We are as guilty as she! Ruth cried it within him and at all of Indi. She walked the streets of Rilemi with Jilla, a part of the admission and the acknowledgement – and Spock understood the emotion that had been crushing him all day. My doing, he agreed. It was treachery to You keep her alive. He realized that he was addressing Aema and his mind shuddered. He forced coherency back to his thoughts, discerning what had happened. Jilla had taken a religious leave. She had returned to Indi. Her Vulcan alteration had left a link, a proto-bond to him, and his recent contact with Ruth had left the keheil vulnerable. She was experiencing everything that was happening on Indi.

It was appropriate, somehow, this sharing of guilt, but it was also, he knew, mortally dangerous. Ruth could not be allowed to sink too deeply, lest her identity submerge further and further, past all recall. He cried desperately to her, Ruth, not Jilla; Antari, not Indiian; keheil, not telmnor; Zehara, not Aema…

She grabbed onto his thoughts, begging for reassurance, truth, being. He gave it unstintingly. The damnation belongs to another, we are only witnesses. Come with me.

“Cold.”

Spock blinked and found himself staring into Ruth’s purple eyes. Bruised, he thought. The color is like a bruise.

“Cold,” she repeated, and her voice was a child’s. She brought her left fist to her chest, cradling it. “It burns, like ice,” she explained.

He heard a hiss and looked up. McCoy was removing a hypospray from Ruth’s arm. The doctor refused to meet Spock’s gaze.

“We heard,” he said. “Too much. She’ll sleep for a while. That might help.”

Spock nodded. “I will wait with her, Doctor,” he said.

“That’s not a good idea, Mr. Spock,” M’Benga put in. His concerned face belied the need for explanation.

“Very well. I will be in my quarters.”

McCoy nodded, then said, “Spock… how will Mrs. Majiir…”

“With the strength that is uniquely hers,” Spock replied. “We must put our hope in that.” He turned and moved heavily through the Sickbay door.

After McCoy had been forced to leave the game by what he described as “Ben’s ability to smell a full house,” things broke up fairly quickly. With the last of the players out the door, Sulu was again alone. If he’d been in the proper frame of mind, he could have been amused by how quickly he’d gotten used to Jilla’s presence in his quarters. Our quarters, he corrected. It had been less than four days since she’d taken off in a Chutzpah for no good reason that she would tell him, and she wasn’t expected back for another three. Four days and it feels like an eternity. Gods, I miss her! He wandered around the cabin, feeling slightly silly as he touched her lyrette, her drafting tools, her clothing and jewelry. He needed some sense of her. It was the only thing that calmed the aching inside him.

He shook off the threatening melancholy with a deep sigh. Jesus, you’ve got it bad, Roy, as someone once said. And speaking of someone… He glanced at the chronometer. Ruth had promised to drop by after watch, but she was late. Probably some last minute thing Spock wanted her to finish, he thought with a shrug. He took a fresh pipe of Rigellian over to the bed and swung the reader into a comfortable position, trying to pass the time until she arrived. When the doorbell chimed moments after he’d started re-reading the collected works of Shakespeare, he called a cheerful “come.” But when he switched off the reader and looked up, it was Pavel Chekov who stood inside the door, not Ruth. And he looked as serious as if he were on the Bridge during a red alert.

The ache within him sharpened. “What is it?” he asked as he sprang tensely to his feet.

“Ruth fainted,” Pavel said.

“She what?”

“It happened so fast, Mr. Spock grabbed her and took her to Sickbay without giving anyone the con.”

Sulu raced out the door, barely hearing Pavel’s, “I thought you would like to know.”

When he reached Sickbay, McCoy was helping Ruth to her feet. “Doc, is she all right?” he asked anxiously, moving next to her to offer his aid. At his voice, Ruth gasped, clutching her left hand close to her chest and burying her face against McCoy. Her shudder was visible, and it cut through him like a knife. “Ruth?” Sulu said softly.

“I’m all right,” she rasped, and above her head, McCoy shook his. “I am, too,” she repeated, with a glare at McCoy, sounding a little more like herself. Then she looked at him, giving a wan smile. But the eyes that met his were not the warm violet he knew so well. They were pale, almost colorless wells that radiated ice. A million points of cold all converged into one bitter torment. He shivered, not wanting to understand. “What happened to your hand?” he said instead.

She blinked at him. “It hurts,” she answered, and her gaze dropped. “Forgive me,” she whispered.

He had heard that tone before, but not from Ruth. It had sighed up at him with wide, worshipping grey eyes. It had begged, “don’t go!” from a Sickbay bed. It asked in innocent wonder, “you want me!” as silky, hesitant fingers stroked his flesh. It moaned “D’Artagnan!” in a murmur of urgent passion.

No.

Then he forced himself to look into the haunted eyes again, and there was no doubt. “Left hand,” he rasped, then suddenly grabbed Ruth’s wrist, forcing the clenched fingers open. He traced a slash across her palm with one swift, savage movement and she cried out. The sound was terror and anguish and his own voice was hoarse and grief-stricken.

“She went to Indi, didn’t she?”

The empty guilt that stared at him from Ruth’s eyes was all the answer he needed.

He closed his eyes, wanting to scream, to go to her, to face all of Indi with her. But that wasn’t permitted. He knew Indiian custom well enough, had spent a long, ardent year studying it in all its facets. He knew what she was doing, what she had to do… Why didn’t I see it? Why didn’t she tell me? I could have at least been with her on the journey, if not at the ritual…

No. She wouldn’t want that. She wouldn’t want me to know what she’d done. It would only shame her more, make it that much harder. Better to let it be until she comes back…

If she intends to come back.

He started to tremble with the horror of that thought. No, she has to come back. Indi doesn’t permit suicide for telmnori, and she couldn’t face Aema yet anyway. She’ll be back. We’ll have time. And with time, I can help lift some of the anguish. Hell is inevitable, but for as long as we live, I can love her and keep the fear of eternity from dominating her life.

He quickly looked up for Ruth, but she was gone. “I sent her home, Sulu,” McCoy said softly. He nodded and moved out of Sickbay as if in a dream. When he got into the turbolift, a new thought struck him, one that filled his heart with cold dismay.

If she’ll let me.

Gods, what do I do if she won’t?

Spock sat in his quarters, his hands clenched tightly together, concentrating fiercely on controlling the shame that filled his mind. His left palm was burning and there was an ice in his heart that would not be banished. He had researched Indiian rituals, and now knew precisely what Jilla was doing, the steps she must take to complete the ceremony of damnation. That she had not undergone the telin-arin after having sexual relations with him was not lost on him, but, oddly enough, it did not diminish his sense of guilt. She damned herself for Sulu, he knew, but relentless logic reminded him that it was he who had damned her. He felt her pain as tangibly as if he walked with her. But that, he knew, was not proper. He was not damned, as Sulu was not. They had not vowed. They had given up nothing, while Jilla sacrificed all. That was the bitter glue which kept his tortured hands clasped together. His mind cried out to her, knowing she could not hear him… and if she could, would you wish the increased agony your tia would give her? Had I known fully what I did, rilain, I would have let you die free!

At the sound of the door chime, his voice called “come” automatically, though his attention did not waver from the torment in his mind. The bolt of new fire into his stinging palm told him who his visitor was, and he looked up. Ruth’s eyes were haunted, her right hand still clutched at her left wrist, her voice still the little girl’s.

“I don’t want to be alone.”

He nodded, and she came and sat beside him, her knees drawn up. After a long silence, she spoke again.

“It hurts.”

“Yes,” he agreed.

“How can she do it?”

“She does what she must.”

She shuddered. “I couldn’t.”

“Nor I,” Spock admitted softly, he turned his head slightly, to look at her. “Does Mr. Sulu know?”

“He didn’t,” Ruth replied. “He does now. He heard I was sick and came to Sickbay. Once he saw what was wrong with me, he didn’t have to be told. He knows Indiian custom.” She suddenly got up, pacing nervously. She seemed lost in private, anxious reverie, and his thoughts again turned inward.

After bare moments, quick fear rose in the back of his mind; the same sensation that had propelled him to action on the Bridge and in Sickbay. He glanced up, his gaze taking in the whole of the cabin in one almost fevered sweep.

He moved, twisting his aro’din from Ruth’s hand seconds before the thin blade slashed across her left palm.

She stared up at him blankly, only the billions of icy eyes shining from hers, then blinked and glanced down at his hand, and hers. "What did I…?" she began, then inhaled sharply.

“Yes,” he said, and was very suddenly and not at all uneasily holding her in a tight embrace of shared remorse. It lasted only brief seconds, then both drew away.

“Can I borrow your lyrette?” she asked.

He nodded, and went back to sit on the bed, slowly rubbing his palms as if to erase the pain freezing there. Then his hands clenched again and he listened to the frantic music that sounded in time with the cries of Indiian voices.

He didn’t know how long Ruth had played. But he was aware of the fading of the lyrette’s reverberance on a minor dissonance of hollow, empty agony. The silence was expectant, then Ruth’s soft, childish voice asked hesitantly, “Can I stay?”

He knew what she meant. The nightmares would come, and only another telepath could aid her when they did. She who intrudes on my dreams. Perhaps, dei’larr’ei, I can return a measure of what you gave me. “Yes,” he said, and she moved next to him, the pain flowing between them. Then she whispered, “sleep,” and as the drowsiness conquered him, he was aware that she curled herself into his arms, her left hand cradled protectively between them.

The nightmares came, furious, often. They spent the hours clutching blindly together, seeking contact, offering it. You are Ruth. You are Spock. Reassurance, being, identity given a thousand times to combat the emptiness of Jilla’s misery.

How long? Ruth asked.

Two more days, Spock replied.

Alone in a shuttle? Ruth grieved.

She needs the time to regain herself, Spock assured.

Telmnor usually dies within a year, Ruth feared.

On Indi and repentant. She is neither. And there is Sulu, Spock explained.

It hurts! Ruth screamed.

It hurts, Spock echoed.

They woke still enfolded in each others’ arms. Ruth thanked him and quickly left. She had left his lyrette on the chair, and as he went to replace it in its stand, his gaze caught sight of the aro’din lying on the shelf that protruded from the bulkhead. There were blood stains on it. Red blood. He remembered with grieving clarity that there had been a moment when he’d realized she was no longer in his arms, but before he could come fully awake, she had returned. His sorrow was silent as he carefully cleaned the blade and returned it to the display of ceremonial weapons that decorated one wall of his cabin.

“Miss Valley, I heard you were taken ill,” Captain Kirk said as she came onto the Bridge.

“Nothing I can’t handle, sir,” she returned, but she was careful not to let him see her eyes.

The Chutzpah was maneuvering gracefully into the hangar deck of the Enterprise when Jilla realized she was back. She had been unaware of her surroundings for the entire trip from Indi, and how she had piloted the shuttle, she did not know. How she had managed to keep from soaring into Zindar’s scarlet agony, or the white torture of Za’Faran, she did not know. Had it really been her intention to do so? Telmnori, how would you have dared? Then she covered her face with her hands, her left palm burning against her cheek. It is done, she told herself, done, and you are lost to your people, lost to Selar for all eternity. My husband, may Aema have mercy!

She moved to the hatch of the craft, waiting for the green light just above it to signal that pressurization was complete. Then she realized that she hadn’t changed from the brown dress she had worn throughout the telin-arin. The thought brought her pain back full force, and she bowed her head, tears again filling her eyes and the hatch slid open.

A hand reached in to help her out of the craft and she shrank from its touch. Scotty’s voice said, “What’s wrong with ye, lassie?” and she moaned helplessly. She stumbled out of the shuttle, trembling, and strong, gentle hands grabbed her shoulders. “Darlin’ girl, what is it?” Scotty repeated worriedly. She glanced up, catching the concern in his eyes, then sobbed and broke free, heading for the door to the bay. His voice called her name and she screamed inside herself and the door opened before she reached it. She looked up and froze, pounding agony searing into her palm and her eyes.

Sulu, Spock and Ruth stood waiting for her. Anguished understanding flooded from them with the same palpable reality as her shame and cold non-being. The eyes of Indi condemned her from Ruth’s haunted gaze. Selar’s grief lay in Spock’s dark sorrow. And worst of all, her own damnation taunted her from the reflection in Sulu’s aching ebony.

She screamed, no longer just in her own mind, and pushed blindly past them, tearing away from the hands that tried to grab her. She ran, desperate to find someplace in all the universe where she could hide from the torment of telmnori.

“Jilla!” Sulu cried as she fled past him. He started to go after her, but Spock’s hand grasped his arm.

“Leave her,” he said hoarsely. “She is not yet real, not even to herself. To touch her, to acknowledge her existence will cause her more pain than she is prepared to deal with. Surely you know that.”

“She’s hurting,” Sulu moaned, “gods, she’s hurting…”

Ruth’s arms came around him. “I know,” she sobbed quietly, “but Spock is right. Give her time.”

Sulu held onto her, but his voice was agonized as he rasped, “Time? She’s got all eternity, Ruth. All eternity.”

It had been hours. Sulu was more than shocked at the sight that greeted him when he at last returned to his quarters. He’d gone through the entire ship looking for Jilla to no avail. He wanted, needed to comfort her, to drive back the terror that had filled her when she looked at him in the shuttle bay. He was desperate to know that he could. Finally, he’d given up, despairing, aching – terrified.

And she was there, lying on their bed, naked, a silver-dusted pearl against the fabric of the bedclothes. Her child’s face was ravaged, streaked with tears, her eyes wells of pain and agony as she looked up at him. He moaned her name, and her lips formed a silent plea of one word:

D’Artagnan.

He raced to her, his own tears clouding his vision. She clung to him, her body trembling with soundless sobbing, but she moved against him urgently, her hands clawing at his clothing. The joy and relief that she still wanted him made him forget her weeping. He pulled off his uniform, caressed her, kissed her – and her legs parted and she begged, “now!”

He complied with all the force her tone demanded. Her response was wild, as though they were on still on Alcon with an aphrodisiac pumping through them. He shuddered with the hedonistic pleasure, her name prayer and entreaty on his lips.

She began moaning and the sound intensified his passion – but there was degradation and terror and raw agony in the cries. It seared into him, a part of him thriving, hungering for it, but the part that was filled with anguished regret was stronger, and he tried to pull away. Her arms locked around his neck, her legs around his waist and she hissed, “no!” in a tone of wracking torment. She drowned out his questions with a litany of “go on, go on!”

Confusion tore at him, but hunger won out and he drove into her, filling his thoughts with unrestrained, undiminished, complete, accepting devotion. Feel it, he begged her, know it, I love you, I love you!

Her palm was pressed against his shoulder-blade, and he cried out as the glacial fire pierced his flesh. She moaned louder, a desolate, tortured sound, and the pain intensified. His body was working feverishly, bringing them both to a frantic climax and as it broke over them, a bolt of hot agony shot from his shoulder to somewhere in the pit of his stomach and Jilla screamed “Damn me!”

The words tore a cry of pain and grief from him and he collapsed on top of her. Tears fell hopelessly down his cheeks, meeting, mingling with hers. She held to him, sobbing, “It hurts, Aema, Sulu, it hurts!” and he let her fingers clutch at him, ignoring the bite of her nails and the slash of fire from her palm.

“I know,” he told her in whispers of comfort, “it hurts, I know. I’m sorry, baby, I love you, I know.”

She cried herself to sleep in his arms and he held her far into the night, stroking the tangled burgundy of her hair.

Spock stood up from the con as Jim stepped onto the Bridge. “Good morning ladies, gentlemen,” the Captain said.

Ruth murmured, “’morning, Captain,” at the same time as Sulu’s, “’morning, sir,” and Jilla’s “good morning, Captain Kirk.” Jim smiled.

“Status?” he requested, then turned to Engineering. “How was your leave, Mrs. Majiir?”

Ruth caught Sulu’s eyes, and he nodded an ‘okay.’

“As I expected, Captain,” was Jilla’s reply.

“Well, we’re glad to have you back.”

“Yes, sir. Thank you, sir.”

Ruth rose from her seat, handing the captain a clipboard. “Duty roster, sir,” she said.

“Thank you, Miss Valley.” Jim turned to the library computer. “Spock, has Canti confirmed our consignment of minerals?”

“Yes, Captain,” Spock replied. “All negotiations were successfully completed. The handling of delivery should be routine.”

“E.T.A.?” Jim asked.

“Seven hours, thirty-six minutes,” Sulu responded.

Jim studied the roster, and the turbolift door opened. “Lassie,“ Scott’s voice said to Jilla, “you might want to get down to the shuttle bay. Mrraal’s tinkerin’ with the Chutzpah.”

Ruth scowled over at Jilla. “Now what does he think …” she began.

“Since it made the trip to…” Jilla countered immediately.

“But you know he’ll just…”

“I will offer my…”

“I’ll have to help if…”

“Captain, may I have permission…”

“Boss, you don’t really need…”

“Go on, both of you!” Jim growled good-naturedly.

“Thank you, sir,” came in unison and Jim heard Sulu and Kevin Riley’s shared chuckle. He glanced at Spock’s raised eyebrows and chuckled himself.

“By the way, Mrs. Majiir,” he said to the turbolift, “you’ll be in the landing party.”

“Yes, sir,” floated back to him as the door hissed softly closed.

To go to the next story in chronological sequence, click here