The only information he had on the alien vessel was what he had gathered through a series of short, rapid scans. He did, however, have a preliminary attempt at a floor plan, and the environment had seemed to be within the boundaries of Earth-normal conditions—in other words, tolerable.

Spock chose a large, empty room which showed no life-forms and which he had tentatively identified as an unused cargo hold. He gave the coordinates to Transporter Chief Kyle, and, after verifying that the Silmaril’s ship still had its shields down, he beamed over. He was armed only with a tricorder and a communicator. It was still just possible that his conclusions were wrong—and, if so, he didn’t want them to even remotely suspect him to be a threat.

Perhaps he had been too preoccupied with the rest of the puzzle to have put some of the other pieces together: the heat-radiating fins on the side of the mother ship and the shuttle; the insulated, highly reflective clothing which the observers wore; the constant glowing of their skin. All mechanisms, some natural, some artificial, designed to keep heat out, or to radiate away, with as much efficiency as physics allowed, all heat possible. Such an extreme need to radiate away heat was inconsistent with the readings of Earth-normal temperatures within the ship as shown by the sensor scans.

Spock materialized inside a small, bright chamber—not at all the dimly-lit cargo hold he’d expected—and was immediately assaulted by a cold more piercing and extreme than anything he’d ever imagined. The water vapor in his windpipe and lungs froze almost instantly. He had time only for a single, rapid observation before his eyes frosted over: the glowing numbers on the tricorder claimed the temperature was only a few degrees above absolute zero. He wasn’t in a vacuum, which seemed to make no sense, because any known gasses would freeze into crystals, or at least become superfluids, at that temperature. Yet a vacuum would not be sucking the heat from his body like this. Even if he could still see, his muscles had frozen, so he couldn’t adjust his tricorder to take any further readings.

His second-to-last thought was to wonder why it was that he felt something stab him in the back of the neck—shouldn’t his skin have become numb from the cold? The final thing he considered was whether, since his lungs had stopped working, he would freeze to death before he suffocated.

Kirk and McCoy had watched from the Bridge as the alien shuttle joined its mother ship. They waited almost half an hour, but nothing further happened. Finally, they went to Kirk’s quarters and waited some more. McCoy insisted they had to get something from his office, and they went there. He pulled out a bottle of brandy to help them wait.

“Doesn’t make sense,” Kirk said, reclining on one of the diagnostic couches. “They have to have found him by now. It’s been almost two hours. If they didn’t know he’s aboard, they’d’ve left by now.”

“Don’t worry so much,” McCoy advised. He pulled a chair over near the couch, and reached for the bottle of brandy next to the intercom on the little table nearby. “Spock’s probably teachin’ ‘em chess. Hope so. Love to see him lose, just once.”

“I shouldn’t have let him go, Bones. I knew it was dangerous.”

“Hell, Spocko knew it, too. Knows. Whatever. That’s part of Fleet. You know that, too. Every time we beam down to a new planet, we take that chance. Hell, ever’ time we get in the transporter and have our atoms scattered halfway across a star system, we take that chance. Any old minor screw-up in the engines could vaporize us all any second—and ever’ time Scotty buys himself a new bottle, we take that chance.”

Kirk looked accusingly at the glass McCoy was refilling for him.

“It’s okay,” McCoy drawled, whispering conspiratorially, “He drinks scotch, not brandy.”

Kirk took another sip. “That’s not the point, Bones. It’s not accidents, or things unknown, which are the problem. I should have known this was wrong. I had all the data. I’ve been overworked, tired. I should not have let this happen to myself.”

“I been tryin’ to tell you you need time off! But do you listen?”

“—and if they’ve been lying to us… well, I let myself be taken in. By the sexiest woman I’ve ever seen. And she didn’t even do anything! Not a single move at seduction or distraction. Just by being around, that’s all it took.”

“If you hadn’t’a been distracted by her, I’da said you were dead. Look, it wouldn’t be the first time a captain’s made a mistake. Or a man’s followed his glands. But Spock was the one who suggested this trip of his, and Spock’s a big boy, and if he was distracted by his glands, I’ll laugh in his face. Now, Jim-boy, you’ve killed two-thirds of this bottle all yourself. Go to sleep. If anythin’ happens, I’ll wake you.”

“You did this to me on purpose.”

“’Course I did. You need to sleep.”

“You’re a hired assassin, aren’t you? Poisoner!” The intercom buzzed. Kirk reached over and flipped it on. “Captain here.”

“How’d you know it ain’t for me?” McCoy objected. “This is my sickbay,” he mumbled.

Uhura’s face appeared on the comscreen. “Captain, the alien shuttle has come back. It’s waiting just outside the hanger bay doors.”

“Well, don’t leave ‘em hangin’ on the stoop, for God’s sake!’ McCoy bellowed. “Let ’em on in!”

“Doctor’s orders,” Kirk relayed. “Have a security team meet me at the shuttle bay." He turned accusingly to McCoy as he flipped off the com. “I’m not alert, Bones. I don’t need this aggravation.” Now where’d he pick up that phrase from?

“You get totin’. I’ll call Chapel to meet us there with a stimulant.”

Kirk grunted and slid off the couch, unsteadily regaining his feet. “Next time you poison me, I’ll have you up on charges.” He stumbled out the door.

Once again, the alien shuttle sat on the hanger deck. Kirk watched as the hatch on top swung up and around, and hardly noticed Chapel by his side with a hypospray. He was distantly aware of McCoy standing beside him, but the doctor said nothing.

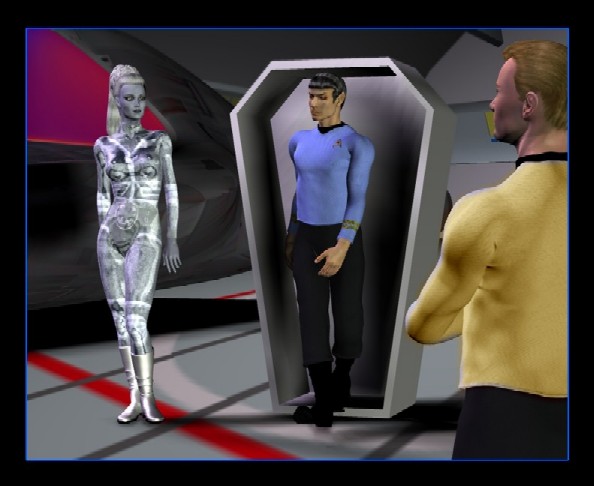

Ilne appeared on top of the shuttle, a large box floating by her side. It looked to Kirk to be the size and shape of a coffin.

She descended the ramp, and stopped, a few feet from Kirk. The box floated beside her, seemingly following of its own accord. “Your science officer is here,” she said, and to Kirk’s slowly-clearing mind her voice seemed like lovely bells on a winter’s night. “We built this device to protect him aboard the shuttle on the journey from our ship.” As she spoke, the box tilted up on one end, and gently sank to the ground. “Apparently your curiosity was not satisfied.”

Kirk managed a smile. “I’ve never known a truly sentient being who’s curiosity ever really was.”

“You shall have your answers, Captain. Enough for now, anyway.” The box slowly swung open “You may not like them,” Ilne finished.

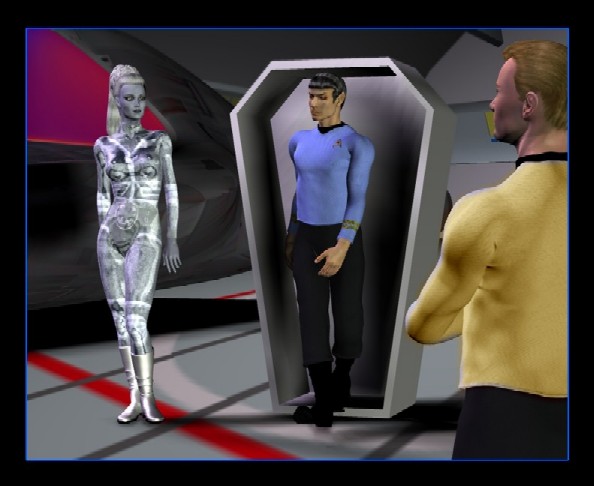

Spock stepped out of the box, and it followed Ilne back up the ramp and into the shuttle. The captain, his first officer, the nurse and doctor, and the small security team all scuttled off the hanger deck as the shuttle lifted upward and started moving back toward the hanger bay doors.

McCoy insisted on subjecting Spock to a complete physical, in spite of the Vulcan’s protestations to Kirk that he was completely healthy. The doctor finally had to almost disappointedly declare that he could find nothing wrong, and the three of them retired to McCoy’s office.

Kirk could contain himself no longer. “Spock, what happened?”

“The sensor readings were all wrong, Captain,” Spock began. “The aliens were aware of our scans from the first, and, as they did not wish us to know their true nature, caused our instruments to give false readings. Thus, our curiosity was being satisfied, far better than if we had simply been blocked. But we were actually receiving no accurate information, not even the knowledge that our sensors were being jammed.

“When I beamed over, I found myself in one of their computer control cubicles…”

“It figures,” said McCoy.

Kirk shushed him, and Spock continued. “Their computer had detected my transporter beam. Its programming did not allow it to risk losing me by cutting the beam or attempting to reflect it back, so instead it confined me to a control cubicle and alerted the crew to my presence. It was there that I finally gained some real information about them, through direct contact with their computer.

“They are more than merely a star-faring race. They were born among the stars, and are more comfortable in the absolute cold of space than in the warmth of a planet. That is why they often returned to their shuttle - to dispel the waste heat their bodies collect when subjected to the temperatures we need in order to maintain our lives.

“They’re immensely old, both as a race and as individuals. If we are infants, the Organians are mere children, and the Silmarils are our great-grandparents.” He paused. “Literally. They are the Star Seeders.”

Kirk’s mouth fell open. McCoy, who had risen to get another bottle, fell back in his chair heavily. “What?” he demanded.

“They are the Star Seeders,” Spock repeated. “Not merely their race—them. Ilne and Rainen were both present at the inception of life on Aleph Corriandus, and on Terra. And Vulcan, Indi, Klingon, and perhaps many dozens of other worlds. They have no Prime Directive, because they do not feel constrained to avoid involving themselves in the lives of their children.”

“But—Spock,” McCoy objected, “that would make them more than a billion—”

“Years old. Yes, Doctor.”

“That’s ridiculous Spock, even coming from you. A living being can’t possibly survive that long.”

“Doctor, at the temperatures of interstellar space—two or three degrees absolute—there is nothing to age them. Their nervous systems become superconductors. They can—literally—live forever.”

Kirk whistled. “Spock, that’s incredible.”

McCoy cleared his throat. “So, that’s their natural habitat? Is their ship like that? How could you survive?”

Spock raised his eyebrows. “I couldn’t, of course, not for more than a few minutes. In that time, the computer made contact with me through my spinal chord, in an attempt to learn how to—preserve me properly. They are a highly ethical species, and their computer was compelled to attempt to save my life. As my body rapidly froze, my nervous system began nearly to superconduct, and the information flowed through me from the computer at nearly the speed of light. I obtained the information I just gave you. This lasted only a short time, however, before I died.”

Kirk stood up. “You what?”

“I died, Captain. Of course. No one of my race or yours could possibly survive that cold. But the Seeders have empathic healing powers even beyond those of the Antaris. And my body was perfectly preserved, utterly undamaged.” Spock almost smiled. “The Silmarils have all the powers and gifts of any race we know of, and more, I’m sure. Our abilities come from them—are inherited from them. They are the gods.”

Kirk cleared his throat uncomfortably. “That’s not what you said before, when you were leaving to sneak onto their vessel.”

“I said I did not believe they were gods. And they are not, not in the sense of being omniscient or omnipotent, or being the creators or rulers of the Universe. Like us, they are limited and they are fallible, though their limits are far beyond ours, and the things at which they would fail—or succeed—are far greater things. But in another, and very real, sense, they are the creators and essence of my race, and yours, and many others.”

“What I still don’t get,” said McCoy, “is this business about the Prime Directive. Why did they make such a big point about it?”

Spock sighed. “You and the rest of the Starfleet Science Academy were quite right, Doctor. Different life forms which evolved on different planets would be irreducibly—different, even if begun from the same original source. This was the weakness in the theories of the Vulcan Science Academy. And yet, there was so much evidence which seemed to point toward the existence of Seeders. The answer was there, and we didn’t see it.

“Parallel social evolution is even less likely than parallel biological evolution. Yet there are many similar societies scattered throughout the galaxy. How could this be? The answer is obvious, and always should have been. The Seeders are still here. And they have always been here. They pushed our evolution into chosen directions, making sure similar—and compatible—life forms, and even similar cultures, developed on so many worlds. They are no longer just Seeders. They are become Cultivators and Weeders. They have—influenced our development from the beginning.

“And now, their seedlings, so long cultivated, have begin to bear fruit. But there are so few of the Seeders, and so many seedlings. The Silmarils are spread too thin, and no longer have the time to help—”

“Wait a minute,” McCoy interrupted again. “You mean, they were there all along?”

Kirk cleared his throat: “They didn’t assimilate us into their culture, or even let us know they exist. Didn’t Rainen say something like that?”

“Yes, Captain, he did. And he was the reason your race survived the Eugenics Wars.”

“But why?” Kirk asked. “What is this all for?”

Spock closed his eyes for a moment. “That, I do not know. Not with any certainty. But I sensed some — vast threat to the galaxy. The Seeders have known of it for millions of years. And now, their time is running short, and there is not enough time for them to complete their cultivation.”

“How short?”

Spock shook his head. “Short—for them. It could be millennia. But they need our help. They desperately need the Federation to repeal—or at least, modify—the Prime Directive.”

Kirk looked down, then at Spock, then McCoy. It explained so much. They are so attractive, he thought, because they are what we are meant to be. They are making us—in their image— so that we can help them do—whatever it is they need us to do.

“Well,” he said finally, “we’d better get moving, if all we’ve got is a few thousand years.”

Kirk had trouble getting to sleep that night. He remembered something the Organians had told him—that one day, the Federation and the Klingons would work together. How much did they know?

The Klingons—are they truly our cousins?

Not, not cousins. Brothers. The black sheep of the family.

We’d better start believing, Kirk thought sleepily, all that crap we preach about brotherhood. Or just wait till your father gets home.

What kind of report do I make to Starfleet? ‘I’ve met the gods, and they’re pissed.’ Will any of this seem so real, so certain, in the morning?

He finally fell asleep, wondering if he’d ever feel attracted to a Klingon woman.

Admiral Rhonda Brezhnova went through Kirk’s report for the fourth time, then sat back to think about it.

Kirk was right to send it here first. And in a tight-security beam. The very idea of eliminating—or even amending – the Prime Directive would be enough to throw the Federation councils into fits. Any proposal of that nature would get lost in committees and investigations and never be seen again. Why, the whole idea was contrary to the very principles the Federation stood for—the rights of self-determination, of non-interference—

And yet, if it were true—

If it were true, it would start a major panic. For one thing, the question of the origin and development of life on dozens of worlds would be settled, once and for all. The Admiral wondered how many of the galaxy’s religions could survive that.

And even if it were true, there was, thus far, no evidence whatever that the Seeders’ interests were at all in line with the Federation’s. Perhaps it was the Silmarils’ policy which should be changed.

One way or another, what was needed was more information. If this report was somehow in error, determination of that now would prevent a lot of unneeded hassle. And probably save a few commissions. And if the report was accurate, the nature of the Seeders’ intentions and purposes would be vital knowledge. A full report was needed, including incontrovertible proof of he Seeders’ existence and identity; the exact nature and time of the threat to the galaxy which they were working against; detailed recommendations for action on specific worlds, should repeal of the Prime Directive be suggested; whether and how to approach the Klingons with this information, and the Romulans, and Gorns and Tholians and Havens and who knew how many other unfriendly or neutral races—

If repeal of the Prime Directive was to be recommended, the only way to accomplish it would be to swamp the Federation councils with so many thorough and detailed reports and proposals that it couldn’t possibly be ignored or put off. And then to push hard. And fast.

And, keep it absolutely secret until then. The best and fastest way to kill it would be to let it out before the mass of proposals were ready.

So far, only a handful of people know—the Admiral, and three of the senior officers of the Enterprise. Kirk’s preliminary reports had been filed with the Archives and the Science Academy and everywhere else preliminary reports are supposed to be filed, but these reports, by themselves, were more mysterious than informative. A follow-up report would have to be included, but something could be thrown together saying that the Seeders—excuse me, Silmarils—had finally just gotten bored and gone home. Or words to that effect. Spock would object—Vulcans were so damned ethical!—but Spock would follow orders. And until things changed, the Prime Directive remains untouched—and Kirk would have to be made to understand that.

It was possible, of course, that the Vulcan Science Academy would get hold of the preliminary reports and come to the same conclusions that Spock had reached. But, like Spock before beaming to the alien ship, they’d lack proof and be unwilling to speculate. They would, however, be powerful allies once the proper information had been gathered—assuming Spock hadn’t been lied to. Though they wouldn’t like the idea of repealing the Prime Directive any more than anyone else would, they would be happy as all get-out at the thought of having their theories about the Seeders finally confirmed.

The only problem was gathering the evidence. A special investigative/exploratory task force would have to be assembled. A small scout ship, with a crew of at most a dozen, turned loose with orders only to find out as much as possible. And not to come back until they had a definite answer. And there could be no direct communication with the team, no progress reports. Or calls for help. And neither the ship nor the crew nor any supplies could come from Fleet. Too easy to trace.

And it should be a mixed crew, both for a good variety of skills, and so that no charges of partisan dominance could be raised later. A Terran, a Vulcan, an Indiian, a Tellurite (if the others could put up with him), an Andorian. An Antari Keheil would be nice (the Admiral grinned: it would also be nice to have one in the crew…) except that the Zehara would probably have to be brought into confidence. The Admiral shuddered.

But no one else could know. Not even Federation Supreme Secretary Anthony Elamas. Especially not Mad Anthony. There was no reason for his ass to be on the line for this. All the responsibility, the Admiral thought, should rest in this office. No excuse for endangering anyone else’s career.

Admiral Brezhnova sat forward and activated the comscreen to call someone in the secretarial pool, thinking, It’s a good thing I’ve known a few traders in my day. First thing I’ve got to do is find and modify something in a warpyacht class.

“This is Rhonda,” she told the answering secretary. “I’ve got a list of people I want you to call for me.”

Let’s get this moving.

Return to Part One

To go to the next story in chronological sequence, click here